When he opened his eyes for a moment, he heard his consort singing, and it distracted him from reality. As she had surely calculated.

The man awoke in his bed of pale greenish-yellow sheets that seemed as though someone had woven them from blades of tall grass in the summer. He brushed at the sheets, which invigorated him and enfolded his body in a cocoon of natural Elfsilk: a thin fiber equivalent or superior to most breeds of magical silkworm, but far rarer.

Beautiful fabric, as hard to harvest as silk, and even harder to grow, with the added disadvantage that it would invariably run out of magic and turn to dust within twenty years, even in the best cases. To half-Elves, that was in no time at all. For other races, it was a fine time. A lifetime.

For a moment, as he sat up before the dawn had yet to rise, the man who had once been mortal looked outside, and he heard a clear voice singing. An operatic pair of lungs raised in song.

“Eithelenidrel?”

He stumbled over to the window and saw her outside. It was dark, the sun still rising on the Palace of the Threefold Oath and the great city of Galdatornil below. The oldest buildings, built to accommodate half-Giants, were as nothing to the ancient Giantseats, vast monoliths of stone that had been repurposed into living quarters for people.

The man could sweep his head and see buildings amongst great trees still growing amidst his home—those that hadn’t gotten up and left a few millennia before. Or he could look down and know that, below his feet, suburban Dwarves and other species were preparing to start their day.

It would have astounded anyone from Earth, or even any other nation in the world. But he had seen this same sight for hundreds of years. So King Nuvityn, ruler of the Kingdom of Myths, [King of Men], Elfwed, King of Myths, Leader of the United Peoples of Erribathe, Manoerhog, just stared ahead at another familiar sight.

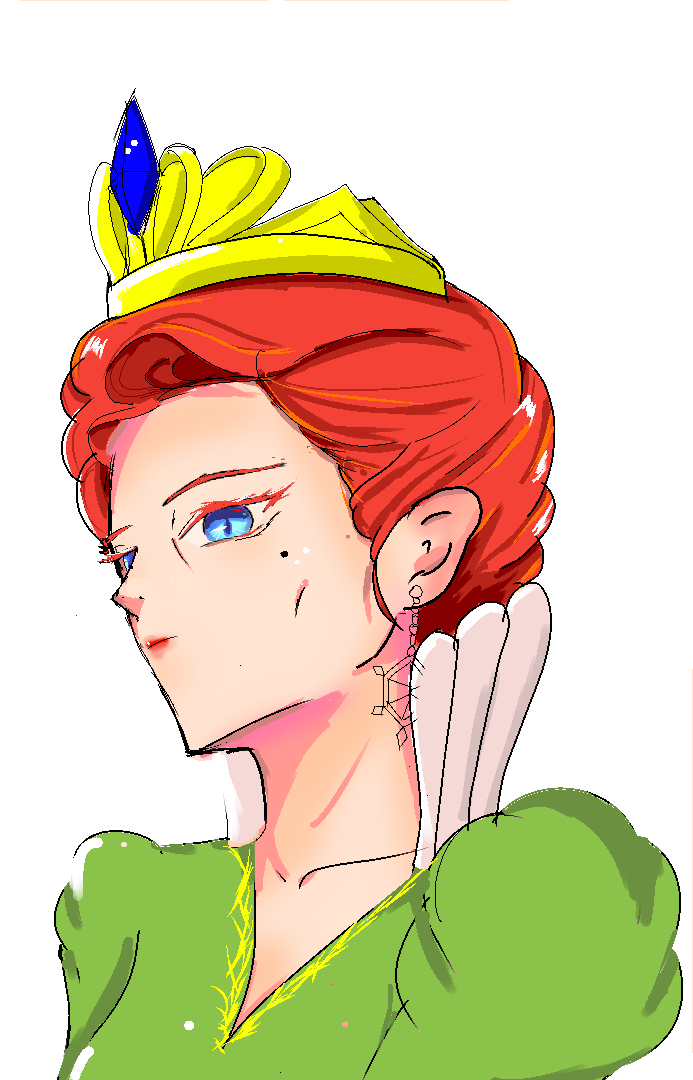

But it had been so long since he’d last heard Queen Eithelenidrel sing. The half-Elf was standing on a tower of the castle that had a view to his window. Her hair was pale red, even if it had begun to gray…far faster than it should. She was singing with a voice to rouse the entire city.

He didn’t know the words. The strange melody sounded half like language, half like the nonsense that [Bards] sometimes made up for fun or to sound grand. Which is what it was. Once—she’d confessed to him that the words weren’t words at all. Just fragmented memories that the half-Elves had failed to preserve, despite their best efforts.

A song.

An Elf’s song. This was their best attempt at remembering what the words had been, apparently.

It was still beautiful. King Nuvityn had heard it before, of course. That was the problem with being so old.

He was two hundred and forty-one years old. The oldest Human in all of Terandria. Possibly second-oldest in the world. The Blighted King was the only person that Nuvityn thought might be older, and if there was a being who had once been Human—undead didn’t count—he didn’t know of them.

He thought he had aged the best. At least, compared to Othius the Fourth. Even now, Nuvityn had a barrel-chested frame and enough muscle to make him look imposing, although his son had always pointed out his growing stomach. His hair was greying, but it still had the same brown as…

The man stared out the window, and an unwelcome understanding gnawed at the edge of his consciousness. Yet for a moment, he still listened.

Yes, he’d done it all. Eaten every conceivable dish. Had every experience, good or ill. Broken bones? Yes. Kissed beautiful women? Undoubtedly. And, accidentally, even a few handsome fellows. It was hard to tell which was which when you were blind drunk.

Seen wonders? Each and every one Terandria had. Partaken of drugs? He could write a list. Fought foes? He’d filled out an Adventurer’s Guild’s bestiary for fun one time. Accidentally fallen onto a rusty spike of metal that had gone straight through his groin and out the other side?

Yep.

The thing about living so long was that everything became…if not predictable, then something you’d experienced before. That was why, after the second time he sat down on a spiny brush filled with needles and felt them sinking into his posterior and other elements of his body, yes, he had screamed. But he’d also thought, ‘ah, not again’.

It took an edge off anything beautiful. The wonders began to pale, and that was a terrible thing. But Nuvityn knew the secret to age that Othius had forgotten:

Even if it was something you’d seen or heard before…if it was rare, it still mattered. So Nuvityn stood at the window and listened.

Eithelenidrel, his consort, the half-Elven Queen of Erribathe, the immortal side to the throne, had sung in his capital exactly three times before this. Over two hundred years they had been wed.

That mattered. Not just because the song captivated him. His eyes fell on her face. She looked better than last he’d seen her. She’d complained that half-Elves her age were hinting about makeup, noticing how she had aged at twice their rate. When was it she’d last come to the palace?

…Twenty-two years ago? She must have come out of the Grovelands. She looked peaceful, now. Not happy, maybe, but she was singing.

It had taken ninety years for her to sing this song the first time. And that was a long time, even for half-Elves. Ninety years for Nuvityn to realize, belatedly, how unhappy she’d been despite her smiles and laughter. When he’d first heard her sing, it had been a revelation.

Nuvityn liked to say that his marriage had had its ups and downs. The first century had been rougher on her; he’d mostly been ignorant of the problems. The second had been more tumultuous for both, as his longer-lived citizens could attest, but they’d come to a rather amicable last thirty years.

The key moment had been when the [King of Men] had finally realized that he’d never sway, convince, or charm Eithelenidrel into necessarily loving him. And that the pact between them was a pact. She had honored it for her people, and he hadn’t realized how much she’d given up.

Half of her lifespan. Her home. Her people—even if half-Elves lived in the capital—and an heir for Erribathe. Not least, the company of a man she hadn’t truly known until they were to be wed.

He’d given her back one of those things, at least in part. Eithelenidrel stayed in the Grovelands and seldom emerged. Not for most royal events; not that Erribathe had many that were annual. It was one of the Restful Three, a nation without need nor complaint.

Eithelenidrel stayed with her people and only came to visit when it was her inclination or at great need. Then she was more like an old friend, and she’d begun to come by with complaints. Or write that her people wanted copies of plays or whatnot.

That was good. It was fairer, and Nuvityn did his best to ensure that adventurers got to any problems in the Grovelands first. And to get her whatever she wanted. He was, after all, still in her debt. Another two centuries and perhaps…well, perhaps he’d make it up to her a bit.

The point was—the song was so rare that it transfixed him in the ten or so minutes she sang there. Then the Queen of Erribathe turned and half-bowed towards him, and he let out a breath he had held…how long, he couldn’t know.

He almost fell out the window of his chambers to his death as he raised a hand to her. He was weak. Lightheaded. Nuvityn caught himself and wondered why he was so thin.

Ah. Right. He hadn’t eaten.

Because his son was dead.

Oh.

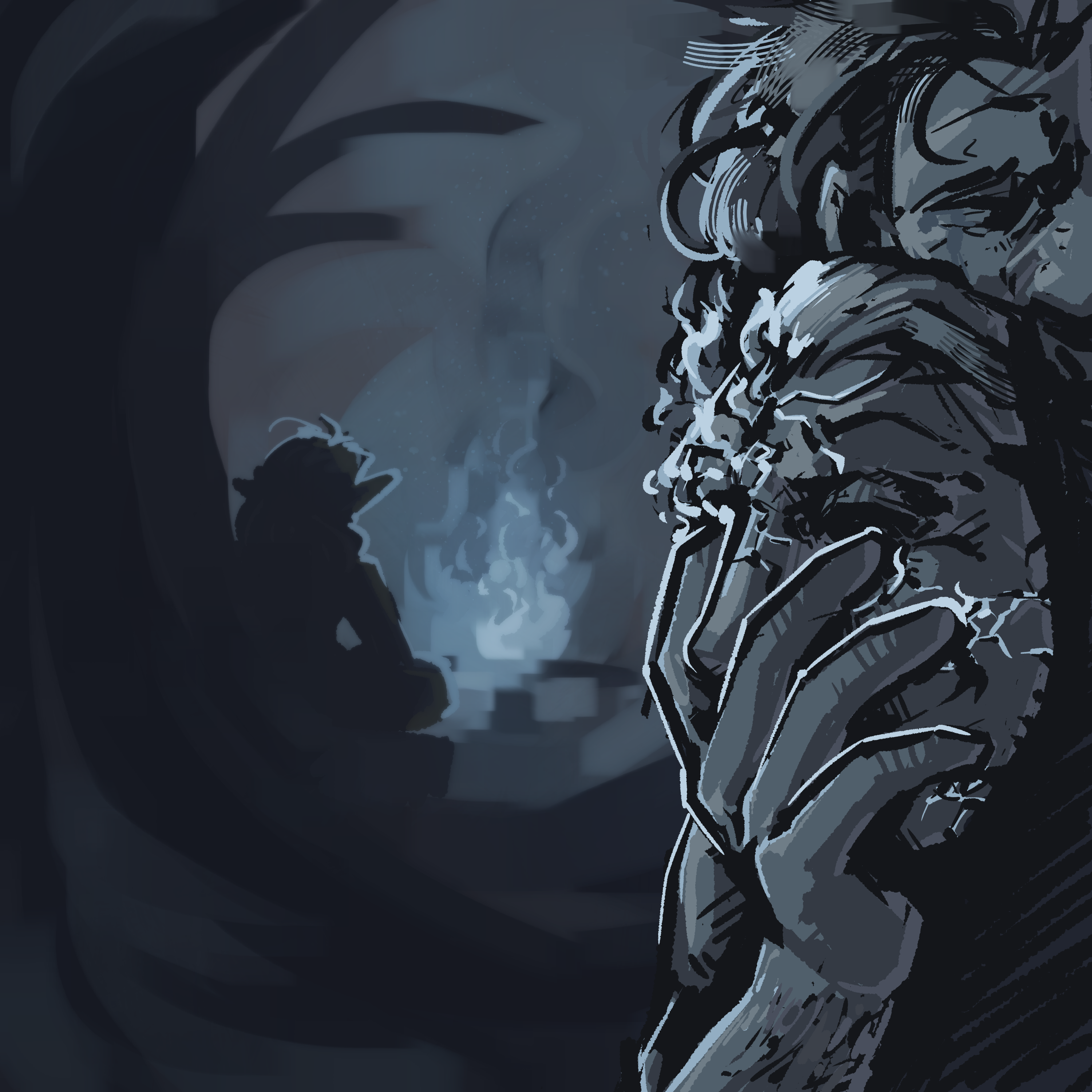

For ten blissful minutes, the King of Erribathe had forgotten it. Not ‘forgotten’, but let it slip from the fore of his mind. Now, he stood there, and weariness sank over him like a great shroud as large as the palace. Pulling him down. Like the depths of the oceans that had claimed Iradoren’s body.

It was terribly cold and dark down there. Iradoren should have been brought back, at least, to be laid in his homeland’s soil. Nuvityn passed a hand over his eyes, and he saw it again and ever again.

That look of fury over his son’s face. Holding the sword of kings, poised to run through a [Knight] on the ground. Why? Why are you—?

Then a look of confusion. Agony, and the terrible sight of a bloody blade moving through his chest, piercing armor that should have kept him proof against any blade. A young woman’s dispassionate face, blank to his identity, heedless, pushing him aside as he fell.

Erin Solstice.

The King of Men stood there, and the Queen of Erribathe raised her head and saw his stricken expression. She wiped at her own eyes briefly. Then began to walk across the tower’s edge towards him. He bowed, then, and wearily straightened as his servants peeked at the frail [King] with worry.

Doubtless, they’d orchestrated part of this. He let them prepare him for breakfast. But all he said was—

“My son is dead.”

Day after day that passed, over a month now, and he continued to hope it had been a dream. But though he was many things—King of Myths, half-immortal, heir to the Hundred Families, Manoerhog—

Nuvityn had been Iradoren’s father.

He knew now, with hindsight that was so clear and revealed too much—

He had probably been a poor one.

Thus, Nuvityn began another day.

——

“Your Majesty. Will you eat?”

“Mayhaps.”

It was a sign of King Nuvityn’s grief that even with a table filled with his favorite foods, he merely picked at his plate. His courts were largely informal; his trusted advisors came and went since the matters of state seldom called for their great expertise.

Right now, almost all of them were present, because the hour called for it. Erribathe had lost its heir, Iradoren, and its colony dreams were in jeopardy. There was another world—Earth—and perhaps most crucially of all at this moment, Nuvityn might just starve himself to death.

“We can ill-afford you passing, Nuvityn. Have you no appetite?”

Queen Eithelenidrel looked at him, and the man blinked at her.

“Have you?”

She was eating a traditional half-Elven dish: a salad. Eithelenidrel was one of those half-Elves who’d forsworn meat. Her salad was made up of flowers, which she was eating petal by petal.

The secret was the nectar, which was sweet. Nuvityn saw her eating more or less at the same pace as normal, which meant breakfast was going to take thirty minutes if she didn’t talk. She looked—decent.

He knew he seemed half-dead himself. The question was, of course, ‘can you eat?’

Their son was dead. Eithelenidrel looked at him, and he again saw those tears he’d seen behind her gaze. But she determinedly chewed on another flower petal.

“I was resigned to it the moment he was born. I wept half my tears then. The same, I would imagine, for Aradien. We outlive our Human counterparts.”

That was true. Nuvityn closed his eyes. Exceptions happened, like his father outliving his mother, but that was mostly due to accidents. Even with their shared immortality, the Kings of Erribathe perished most often whether due to battle or simply because they lived lives in the open, entangled with mortal affairs and risks.

A younger, more foolish man would have taken Eithelenidrel’s words as her coping with her grief in her own way and left it at that. The older man realized the words were twice bitter.

She…may not have loved Iradoren like he did. Or she’d deliberately moved her heart away from the boy she had raised. Never borne. Or else Iradoren would have been a half-Elf. Was that the only reason why the two regarded him differently? She had been there from the moment he had been born until he was a grown man. Of course, Iradoren had still visited her regularly, at least once or twice a year.

That is not how most Humans live. But Iradoren was—had been—over seventy years himself. A long, long time. A long childhood, even if he’d looked like a grown man for decades.

It was hard to grow up under the shadow of a [King] who could hold the throne for centuries more. Hard, doubtless, to live in a kingdom content with being one of the Restful Three. Nuvityn knew the feeling of wild yearning to prove Erribathe’s greatness.

Well, in part. His own grandfather had told him he was the most ‘placid’ of Erribathe’s heirs in a long time. Which wasn’t saying much. If it had been an insult, it was probably because Nuvityn had spent decades actually roaming around Erribathe. He’d lived with the Hillfolk, tried his hand at smithing with the Dwarves, even lived off of salads and whatnot with the half-Elves.

His title, Manoerhog, was the first to be granted to a King of Erribathe in three generations, which was astounding to Nuvityn. Not even his son had continued the tradition of facing the giant hogs of the northern kingdom of Taligrit and wrestling them in mud pits.

That was why Nuvityn sometimes had it appended to his royal titles, much to Eithelenidrel’s exasperation. Because it made him, well, unique compared to his father, who’d also been a decent ruler and lived three hundred damned years, or his grandfather, who’d lived nearly five hundred.

Each one had been a great [King]. Skilled in swordplay, wise, had mobilized Erribathe in times of need, etcetera, etcetera. But none of them had been Manoerhog.

A title awarded by the northern kingdom of Taligrit to…well, anyone really. But it was seldom obtained, and even more seldom by a King of Erribathe, though it was customary to take the challenge. Nuvityn had taken it and won it in his youth.

They still remembered him for that.

“Hm?”

Someone had been talking to him. Eithelenidrel glanced at Nuvityn, and for once, she was the one talking and he was the silent one not paying attention.

“The Groveland’s Conclave is worried about the state of the kingdom. Keeping you alive is one reason I am here. Also, because I was genuinely concerned.”

“Were you?”

His head rose, and she half-nodded. Nuvityn was gratified by that and found the energy to spear a link of sausage and chew on it. He normally had a fine appetite.

“Don’t fear for the kingdom. I shan’t name you as the regent if I die.”

“Thank you.”

She smiled at that. Not that there was much of a chance anyways; succession law dictated that the Crown of Myths flowed from male heir to male heir. The Queen Consorts were never chosen to rule except if they needed to as regents before a new heir was old enough.

In Eithelenidrel’s case, she would have rather eaten a whole pork roast each morning than taken the throne. Nuvityn spoke out of the corner of his mouth, wrenching his mind off of…well, anything but reality.

“I have already named Prince Geltheid as the new heir apparent. Does that satisfy the Grovelands? I did not make it public…”

Because it was too difficult and his kingdom was in mourning. Eithelenidrel tilted her head.

“Which lineage is that?”

“Thamed. Dwarves.”

“Oh. I picture a boy learning to smith mithril…”

“Yes. A good lad. Stout of heart and mind. He keeps the holds of the mountains in good order and saw off several Ogre bands half a decade back. He’ll be fine.”

There were other [Princes] of Erribathe. Not so much like Iradoren had been, the obvious successor, but the bloodline of Erribathe was carefully diversified among a few groups, if only to prevent inbreeding. The [Kings] of Erribathe married half-Elves, but the bloodlines never mixed with half-Elves, and lesser [Princes] wed other royalty as they pleased.

If they took the throne, well…that was a tricky thorn that had been navigated many times before. The union mattered, and so there had been polygamist [Kings] of Erribathe. Quite a few, actually.

“Have you met him recently?”

That was a quintessentially half-Elven question, and Nuvityn nodded as he continued to eat the link of sausage.

“He attends the palace several times a year. He’s thoughtful. Until now, he was determined to have us expand our industries and allow newcomers to Erribathe.”

Eithelenidrel made a noise of dismay, and he clarified.

“In the Outer Regions. Nowhere past the Mists. He would rather we turned some of that border into prosperous cities. The older minds won’t like it if he takes the throne, but given Ailendamus rising…”

“…Which one is that? The nation you were complaining about recently?”

“The new one. It was founded just after you were eighty?”

He tried, but Eithelenidrel really didn’t care that much about nations beyond Erribathe that weren’t half-Elven. And sure enough, she snapped her fingers.

“Oh! The ones who established the half-Elven enclaves. We like them?”

“They made war on the Dawn Concordat and swallowed eight nations.”

His wife’s brows snapped together in outrage.

“Ah. Gaiil-Drome’s alliance. Then they are a foe.”

Nuvityn decided to abandon the topic. It wasn’t like he had set Erribathe against them in any real way either. His son had wanted to march Erribathe’s armies on Ailendamus to defend older kingdoms multiple times.

Nuvityn had been forced to order Iradoren to hold, twice, literally by telling the [Generals] to march their armies back the way they’d come. He had believed they could have triumphed or forced Ailendamus to pull out of the war—but at what cost?

Iradoren had been young and never counted those costs. Nor that he could die. Nuvityn could well imagine a war that consumed the lives of tens of thousands of his subjects, despite Erribathe’s might.

No. He had been content—or complacent, as Iradoren threw at him—to watch. Of course, the irony was that the one time he had ever gone back on that vow, lured by ideals of new lands and another world…

Nuvityn’s hand clenched on a mithril fork and bent it. He glanced down at the silverware and dropped it as Eithelenidrel stopped eating. He pushed back his plate, one sausage eaten.

“I am not hungry after all.”

“You should eat. You have shrunken with grief.”

A chorus of his advisors added their voices to that, and Nuvityn shook his head. He glanced around and saw one of his people, an Osverthian woman named Voreca, making a signal to Eithelenidrel.

She was one of the heads of her region, which produced metal and armor for Erribathe’s [Knights]. She was also intelligent and came up with plans, often to get him to do something or, until his passing, to sway Iradoren’s mind.

“Oh. Yes. I brought you something, Nuvityn. This may ease your hunger, if nothing will.”

Eithelenidrel fiddled with a bag of holding. She pulled something out, and Nuvityn saw satisfied smiles on his court’s faces. He peered over as she lifted an object wrapped in, of all things, huge leaves.

“What’s this?”

“It is something the Groveland’s bakers made with direction from the…new children. The ones of Earth.”

Earth. The weary King of Myths’ head rose with interest, despite himself, for that was the one thing that he had never heard nor thought of in his long life.

“Where are the Earth-children? And Aradien, for that matter. Are they safe?”

The Earther children hadn’t been sent in the first colony wave, but they had been given all the hospitality of Erribathe in exchange for their knowledge. And Aradien had survived the fighting, hadn’t she? He wondered what he’d say to her.

Voreca called out in a steady voice.

“Lady Aradien has almost returned to Erribathe, Your Majesty. She has been honoring Prince Iradoren at each nation, which has taken time—and the Earth children are well, if concerned for you. See what they suggested be made.”

“Your lies about their concerns for me are well received, Voreca.”

He grunted as he unwrapped the leaves. Voreca assured him it was not.

“No, they regard you as a [King] among others, Your Majesty. They make flattering comments as though you were a famous ruler from their own stories. This is from those stories.”

“What is it?”

Nuvityn found himself staring at a bunch of, well, pieces of flatbread. They were a bit crumbly, and someone had baked some fruit into them. He turned to Eithelenidrel, and she spoke.

“Elven bread. Waybread. Ah…lembas?”

She said a word in another tongue, and Nuvityn’s ears lit up. His eyes opened wide.

“Bread made by Elves?”

He took a piece and sniffed it, then broke off a part and tasted it. It was good bread. Unleavened and sweetened by the fruit. He took one bite, then another, noting it was filled with something heartening for a traveller.

Tastes like soldier’s bread. It’d be good for campaign. But he had expected…well, he listened as Voreca tried to explain.

“It might not be the same recipe. We only had their concepts to go off of, Your Majesty. But the concept is that there is a bread used by travellers that can fill a man up with a tiny piece.”

Nuvityn stopped eating. He stared at the bread, then heard his stomach rumble despite him having taken several huge bites.

“…Well, that’s a lie. Wait. Is this another idea that isn’t real from Earth?”

He stopped, and the court susurrated. Voreca gave him an innocent look as a scowl drew over Nuvityn’s face.

“Your Majesty? Whatever could you mean?”

Nuvityn took a huge bite out of the ‘lembas’ and tasted what was probably some half-Elven version of lard, syrup—fattening ingredients, dried fruits, and high-quality flour—he washed it down and growled.

“I appreciate the [Bakers] doing their best. But that comes from their stories of Elves, doesn’t it? I’ve talked to the children. They have no idea what Elves are actually like. Their ‘Elves’ are just characters in books or actors played by Humans.”

“What? But I thought—”

Eithelenidrel looked dismayed as she sampled the ‘Elven bread’, and Nuvityn glowered at Voreca, who was hiding a smile.

She had doubtless done this on purpose. Mostly to get a rise out of him and probably to poke fun at Eithelenidrel. The two had a rivalry of kinds, though, frankly, it might have been one-sided on Voreca’s part as Eithelenidrel had never acknowledged her.

Nuvityn liked the children from Earth. He had great sympathy for them being torn from their homes, even if they’d had the luck to land in Erribathe. Their ideas were fascinating, and Iradoren had been so taken with them he’d demanded they buy sulfur and try to make the many things the young men and women talked about.

But all the Elven claptrap annoyed Nuvityn no end. He hadn’t ever met an Elf, of course; even though the last Elf to ever live had wed Erribathe’s first [King]. But Nuvityn’s bloodline was mildly related to hers, and he knew half-Elves.

Real half-Elves. The kind who lived in the oldest villages. The ones with the power of immortality, and he disliked the presumptions that the Earth-children put on them. He especially disliked the, well, frankly speciesist way the Earth-children talked about Elves.

Beautiful, immortal, graceful—all words that could apply to half-Elves. Eithelenidrel certainly might look the part. But didn’t that paint an entire species with one brush?

If you’d ever seen a half-Elf surreptitiously snort a giant booger out of one nostril, you’d realize they were just people like you. Not all of them knew how to shoot a bow; Nuvityn was a better shot than one half-Elf he knew who was over eight hundred years old, and the fellow practiced with a bow constantly.

And what about Dwarves? When he’d asked, one of the ‘experts’, a lad named Ronald, had had a lot to say about Dwarves that was complimentary. Stout of heart, strong, stubborn, good with metal—wait a second.

He had it in his head that all Dwarves were part smith, part warrior, part grudgeful drunkards who liked living in hills and mining for gold. Nuvityn could only explain it as the children having stories of Dwarves and Elves and not ever meeting them as individuals.

It was disappointing to him because it was how many Terandrians acted. Yes, a lot of Dwarves lived in Deríthal-Vel, Dwarfhome, which meant a lot were experts in metallurgy or related to the field. Yes, many half-Elves did practice the bow because it was something they were known for.

Just…was that how you would open a conversation with a member of their species? Would you turn to a Dwarf every time you had a metal-related question?

Nuvityn realized he’d eaten half the bread as he groused about that, and Voreca’s smirk made him drop the bread and rise.

“Eithelenidrel, thank you for the gift. It seems it has roused my spirits. I must be about the duties of Erribathe now. Will you join me?”

“Hmm. No. I did not wish to return to rule. Just to see you well. I will linger a while.”

He nodded at her and bowed, then turned to Voreca. The food after so long felt heavy in his stomach, but reminded of Earthers…his grief seemed to reignite the other emotion slumbering in his chest.

“Voreca. Summon a [Mage] skilled in communication spells, and meet me in the war room. Has word come back yet from the Village of the Spring?”

“Not yet, Your Majesty. We hope for a reply by today if all is well.”

“Good. Then tell me—”

The King of Myths’ eyes narrowed, his hands gripped the table, and his mind flashed back to that moment. That day—those days of seeing Terandria’s armies beset at sea, helpless to do more than lob spells from afar.

“Tell me once again how it came to this.”

He began to stride out of the banquet hall, the heavy weight of pain and reality clinging to him. But if there was one luxury—one among the many thousands—to being King of Erribathe, it was that he had the power to do what he willed.

For better or worse, as his son had always wished and why Nuvityn had been considering relinquishing the throne. To slay any foe, to raise great armies.

But first—he listened a while.

——

“There were three major incidents revolving around Erin Solstice, Your Majesty. Each one occurred chronologically, but her involvement in all three stems back…how long, we cannot say. Knowledge of her is limited.”

“If she hails from another world, it makes sense.”

Nuvityn rested his weight on his hands as he stared at a map of the world, and Voreca and his advisors reconstructed a picture for him. He was no gifted [Strategist] like the late Earl Altestiel.

Ah, a fine man. I met him once, ten years back. Very much like a storm himself, from laughter to tempests.

Another man to mourn. He had sacrificed himself to save Calanfer’s [Princess], Ser Solstice, and so many others. The entire fleet, in truth, but he had been known friends of the…Ivory Five?

Nuvityn consulted some notes spread out to the side. It had taken weeks to get all this intelligence. Erribathe, of course, had informants and networks of intelligence, but it hadn’t been as concerned with the world as most nations.

Establishing links, buying information, and so on had taken time. But they had endless coffers, and the pieces were all here.

“Why would the Earl of Rains have such faith in a man my son wanted so desperately to kill?”

“Your Majesty?”

Voreca stopped, brushing at the silver streaks in her black hair as she hesitated, holding up a mithril pointing stick towards a diagram. Nuvityn shook his head.

“Nevermind. We’ll come to it later. Please, continue.”

He was no great mind. But he could definitely follow the events as she and his people laid them out for him.

“The Winter Solstice—a great battle against undead led by some horrifically powerful [Necromancer].”

“Whom we do not know the identity of. We have scoured the lists of old foes, and we believe it may have been the Putrid One, Your Majesty. But that’s merely supposition based on the Village of the Dead raid.”

A very nervous [Grand Magus] broke in anxiously. The entire table shifted as even one of the [Generals] licked their lips.

“Ten thousand Draugr. An attack worldwide. How—I didn’t even ask about the children. Were any hurt like that Rémi Canada fellow?”

Genuine concern provided a quick distraction. Had an Earther been hurt on the Solstice under his care? A quick shake of the head assured him.

“It was merely Ghouls, Your Majesty. One of them was staying with the hillfolk—the Ghouls wounded two brave citizens who took up arms with the guards to fend them off.”

“Have they already been rewarded?”

Nuvityn got a nod, and the King of Myths rested his weight on the table. And is that woman dead? A foolish question where [Necromancers] were concerned. Best practice was to operate as if they were not.

“Necromancers. Didn’t one attack Noelictus recently? There was a minor incident with that. If the Horns of Hammerad awoke some great foe that the [Innkeeper] took on…I want the Necromancer truly dead. Report any sightings to me.”

Erribathe had failed to kill Az’kerash fully, but they had participated in a number of battles that had defeated him, only for his return a decade later. The thought of another such protracted battle was dire. But what was his other option? To wash his hands of it and let Izril suffer a scourge like that?

Duty impelled Nuvityn to see if that foe could be fought. He put the matter aside as Voreca nodded.

“She may be defeated, Your Majesty. Erin Solstice announced and even challenged her foe to open battle, and it appeared by all accounts the woman was bested. Then, immediately afterwards, an attack by Roshal that left Magnolia Reinhart gravely wounded. An assault on both Walled Cities and the Five Families! Following that, a kidnapping to sea—”

“Hold.”

Nuvityn broke in with a frown, and Voreca paused. He glanced at the icon flashing on Chandrar’s southwestern side. Roshal.

He did not care for them. Did not think of them often as they were banned from Terandria’s shores by and large.

“Are you certain it was Roshal?”

“We are certain, Your Majesty. Their involvement at the end of the Solstice is not well known. Nor does it seem as though all of the Five Families or Walled Cities have pressed their grievances against Roshal.”

“They nearly killed Magnolia Reinhart herself. She is the current scion of House Reinhart, yes?”

That would have led to an all-out war against whoever it was, at least in my father’s time. Nuvityn glanced at one of his [Diplomats] wordlessly, seeking an explanation.

“Roshal has mitigated the damage they caused, Your Majesty. There are factors within the Five Families that seem to indicate Magnolia Reinhart has lost some of her authority. The Walled Cities have lost Chaldion of Pallass; we can expect both groups are disorganized.”

“Even so. I would have thought Roshal, famous for its ‘neutrality’, would have been shouted across the television networks for this attack. Why not?”

Nuvityn listened as his [Diplomat] explained, then sighed. Ah, oh. Right.

Politics were never that simple, within Erribathe or without.

——

Why…was Roshal not at war with the Walled Cities and Five Families? They had launched an unprovoked assault on at least two leading members of the Five Families—three, if you counted Xitegen, and there had been representatives of each family present—as well as on the Drakes.

Throw in the Forgotten Wing company’s forces and the fact that [Assassins] had run rampant in Invrisil, and Liscor, and kidnapped Erin Solstice to sea—and the fighting there—and it was entirely reasonable for multiple nations to currently be watching out in case Roshal decided to kidnap or murder on their lands.

It should have been a political disaster.

It should have been news.

It was not.

Why?

Diplomacy. Soft power.

Shaullile.

In the moments after the attack on Magnolia Reinhart, even as Erin Solstice was aboard The Naga’s Den, and most certainly after the battle at sea, Roshal’s [Diplomats] had worked day and night.

Nevermind the devastation to Roshal itself; they were trying to prevent something just as terrible as Khelt sending another spell against them. Namely—keeping the wrath of multiple world powers from declaring against Roshal.

They had advantages. Magnolia Reinhart’s incapacitation and the freeing of House Reinhart—and the loss of Chaldion—made the job manageable, if not easy.

Within fifty minutes of the attack, a [Diplomat] was striding into a not-a-throne room for an audience with a Drake curled up against the not-a-throne.

The Serpentine Matriarch was not happy to be woken so late at night, but the battle on the Solstice was making her [Strategists] scream, so she’d been half-watching anyways. She glowered at the [Slaver] as they bowed.

“Give me one reason not to expel you from my city this moment. Sharkcaptain Femar, watch for more kidnappers or hired killers.”

“Always, Matriarch.”

The Sharkcaptain was very close to the [Diplomat], who kept his head bowed, sweating as the huge Drake prowled around him. He was grateful he’d secured an audience with just the Matriarch and her loyal bodyguard. Not the entire Admiralty.

The directive had been to not present the offer in the same room with Admiral Asale. And to move fast.

“Great Serpentine Matriarch, what can I say but to throw myself upon your mercy? You have every right to expel myself and every member of Roshal in the city. Nay, to even bar the City of Waves against us, grievous as that would be!”

“I am minded to. Attacking Drakes as we fight against [Necromancers]? Even if it is the Five Families—striking them? Why shouldn’t I?”

The Serpentine Matriarch was young, or looked young, and had the elements of her position about her. Her tail was long, and those who saw her thought she looked less Draconic and more infused by another ancestor of Drakes.

She was prepared, like a viper, to strike, but the [Diplomat] took her off-guard with the next thing he said. The Stitch-man fell to his knees, and Femar lifted his spear, but the [Diplomat] prostrated himself.

“Humble Roshal begs your forgiveness, Serpentine Matriarch, and we shall abide by Zeres’ justified wrath as long as it washes over us! But we beg—beg that you accept a small offering to stay your hand against the worst.”

“Hm?”

The Matriarch frowned, and the [Diplomat] clarified.

“War! Your Serpentine Majesty! Do not send Zeres’ navies to war against Roshal! Spare us only that, and we are prepared to pay any price!”

War? Femar’s brow rose, and despite herself, the Serpentine Matriarch exchanged a glance with the Sharkcaptain. She looked amused, then covered up a smile.

“It had crossed my mind. Why should I hear your request? What…gift is this?”

She was lying. The [Diplomat] knew that.

Zeres was, of all the Walled Cities, the least likely to declare war on Roshal. They had no soldiers at the Solstice. Plus, they had a very good idea how costly a war with one of the other great naval powers would be. The thought hadn’t even crossed the Serpentine Matriarch’s mind.

Even if Pallass and Manus and Salazsar all demanded it, it would have taken weeks for a formal declaration of war to actually come from the Walled Cities—it would have probably just been sanctions or something lesser given that none of their leaders had been hurt by Roshal.

However…if Roshal was panicking that much, the Serpentine Matriarch could press them.

That was her train of logic. Roshal’s? The [Diplomat] had orders straight from Slave Lady Shaullile herself, and he understood what she wanted. So he scrambled to offer Femar a scroll, which the Sharkcaptain inspected, then showed the Serpentine Matriarch.

A gleam of avarice shone in her eyes as she saw the quoted number Roshal would pay just so Zeres didn’t declare war on them.

“That is hardly a suitable recompense for Roshal’s treachery, [Diplomat].”

She hissed softly at him, and he scrambled to prostrate himself again, as if he were terrified.

“I can of course amend—”

“You had better.”

The Serpentine Matriarch kept pressing the ‘panicked’ [Diplomat], and in truth, he was pressed—mostly to look as flustered and terrified as she expected. It was indeed good Admiral Asale wasn’t here. He might have reined in the Serpentine Matriarch, but she pounced on the opportunity as she saw it.

Thirty-six minutes of blistering crossfire from her and Femar, protestations, pleas, outright begging, and terror from him, and he had clothing covered in sweat—and a contract agreeing to the most simple, ludicrously open terms.

Zeres shall not declare war on Roshal for a period of (32) days.

Simple. It did not include the other Walled Cities. It cost Roshal nearly two hundred and eighty thousand gold pieces, a ludicrous sum. Or? An excellent bargain.

The [Diplomat] instantly informed Lailight Scintillation of his success and was told to make sure every single [Slaver] group in Zeres and Izril kept their heads down. His job was done.

——

A rather similar tactic was employed with the Five Families, albeit not as successfully because there was no huge Walled City, but rather, lesser nobles who had to be swayed. Deilan El, Lady Ulva, and the Admiralty of Wellfar were judged rather more canny than the Serpentine Matriarch, though several members of the Admiralty were approached to mixed results.

However, the Drake initiatives became clear when Dragonspeaker Luciva and Wall Lord Ilvriss both petitioned their cities to take immediate ‘offensive diplomatic action’ against Roshal—a Drake term—they had little pushback.

Pallass, indeed, was only slow to ratify the motion because Chaldion was out of the command loop, as was General Duln. But the conversation looked something like this.

Oteslia: We are connected securely, and the First Gardener is apprised.

Fissival: The Three are not all in the room, but we’re listening. Connection secure, even from Wistram.

Manus: Motion to censure Roshal underway. Security Council will review. Pallass?

Pallass: Standby.

Salazsar: Present. The Walled Families are highly unhappy. With Roshal.

Zeres: Dead gods. The Serpentine Matriarch is impatiently awaiting results. Shall we impose sanctions? Ban Roshal’s [Slavers]?

Manus: A report has been submitted to each High Command. Recap is not necessary here; a formal, public complaint of Roshal’s assassination of at least two individuals and kidnapping of an independant is merited. Not to mention attacks on our forces.

Salazsar: How many casualties on our sides? Do we have a headcount? Is Wall Lord Aldonss really dead? As well as General Duln?

Oteslia: Wall Lord Aldonss is dead?

Manus: Casualties are being assessed from Roshal’s interference. Minimal at this time. A full report will be generated through private channels later.

Pallass: We are ready to begin.

Fissival: If they only wounded Magnolia Reinhart, a public protest is our agreement. War or any escalation against Roshal isn’t germane to our goals at this moment.

Salazsar: You weren’t there.

Fissival: We provided fire support! At great cost! Your forces weren’t there, just one Wall Lord. Roshal’s sanctions would have some economic impact.

Oteslia: Stop squabbling, please. The First Gardener is watching this conversation. Oteslia stands in favor of public condemnation, regardless of Roshal’s overtures.

Pallass: Can the [Assassin] claims be substantiated factually?

Manus: Identification of the [Assassins] is difficult. The [Innkeeper] is gone.

Zeres: What [Innkeeper]? We’re not declaring war. In motion of whatever else.

Fissival: Proper factual accounting of the…facts will matter for televised condemnation. Strong verbal condemnation?

Manus: They attacked a joint force of three Walled Cities in the field during a battle that cost multiple leaders’ lives. This was no light act.

Zeres: But it wounded Magnolia Reinhart. So a plus for them.

Oteslia: We are not in support of light condemnation. Especially given Roshal’s attempts to buy peace. All in favor of a public condemnation?

Pallass: Pending the Assembly of Craft’s vote, yes.

Fissival: What? Get High Command to do it. Yes—pending proof of Roshal’s involvement.

Salazsar: General Duln is deceased. So is Strategist Chaldion. Yes from us.

Pallass: Grand Strategist Chaldion not dead, please disregard.

Zeres: No war. Condemn away.

Manus: Oteslia, can you clarify bribery attempts? Yes from Manus.

Oteslia: The First Gardener was petitioned heavily by [Diplomats] to avoid public condemnation. All offers—substantive ones—were, of course, refused.

Salazsar: We can disclose the same directed towards members of our Walled Families. Two bribes were taken; they’ve been ignored.

Fissival: Typical. All bribes ignored. That’s what integrity looks like by the way, Salazsar. Can we get the reports now? How dangerous was that [Necromancer]? As bad as Az’kerash? Worse?

Pallass: Bribery attempts? Standby. Investigating…

Manus: No such attempts were made to members of Manus. The Walled Cities are in no binding contracts with Roshal that will impede continued actions, agreed?

Salazsar: No.

Fissival: Of course not.

Oteslia: No.

Pallass: No. Standby for full confirmation.

Manus: Zeres?

Zeres: We are not engaging in war with Roshal. Zeres has no objections.

Oteslia: That’s oddly worded.

Salazsar: The Admiralty and Serpentine Matriarch have no contracts with Roshal at this time beyond basic trade and entry, correct? Two members of the Walled Families cannot sway any vote and have been excised from any votes regarding Roshal by the Last Defenders of the Wall.

Fissival: Oh, that faction of old Drakes.

Oteslia: Please, Fissival. Unity here.

Zeres: Going to war with Roshal is a ludicrous concept that we wouldn’t engage with. We have no issue.

Fissival: That implies war with Roshal would be an issue.

Pallass: Does Zeres have a contract with Roshal?

Oteslia: Zeres. Were you AWARE of the attack at Liscor?

Zeres: Certainly not!

Manus: Zeres, please connect the Serpentine Matriarch with Dragonspeaker Luciva. Now.

Fissival: The Three are being informed. Zeres, what did you sign?

Zeres: There is no issue. The Serpentine Matriarch is occupied.

Oteslia: The First Gardener has a call for the Serpentine Matriarch as well. Pick up.

Pallass: Pallass may have an issue with members of the Assembly of Crafts accepting gold. High Command still votes ‘yes’.

Salazsar: How much did they pay you for Drake blood?

Zeres: Roshal killed no Drakes.

Manus: Drakes have died as a result of the attack.

Zeres: Roshal has killed no important Drakes. War would be a ridiculously unsound step regardless.

Salazsar: You traitors.

Salazsar: That was Wall Lord Zail, please disregard.

Fissival: No, no, keep going. Fissival’s in rare agreement.

Manus: Zeres, please copy over contract details for review now. And please disclose any other entanglements, by city, now.

Oteslia: None that we know of.

Pallass: Standby. All of them?

Zeres: This is ridiculous. Stop sending communication spells. The Matriarch is busy. There are no entanglements. We don’t even have full proof anyways.

Fissival: How much did they pay you? How much do we get for all this? Because you’re sharing the wealth, right?

Zeres: Standby. Also, Zeres demands proof before it backs any resolution sanctioning Roshal. At all.

And so it went. You didn’t have to be a genius to guess how one city starting an argument to drag down the unity of the six would go.

Well, as Nerul Gemscale would later comment to his nephew, Wall Lord Ilvriss, the chaos caused by Roshal was indeed a genius move. Not least because they’d paid a minimal price to hold up a full-throated roar of outrage from the Drakes.

By the time the Walled Cities did finish an investigation, their complaint was public—but not televised—and, because they couldn’t fully prove it was Roshal, far too light. And weeks after the battle at sea and Solstice.

How many people paid attention to that? How many people put together the Solstice, The Wandering Inn, and the facts of what Roshal had done as opposed to the nation of [Slavers] doing something unpleasant that the Walled Cities were mad about?

The Five Families had much the same issue. House Reinhart, which would normally have gone to war for the attack even if just in words, was suddenly under new management.

“Oh, it’s an outrage. An attack on dear Cousin Magnolia? Roshal will pay for this. Now—how much?”

That was Lady Cecille Reinhart’s exact quote on the matter. Without the support of House Reinhart, the Five Families also weakened their position.

House Veltras instantly and unequivocally announced their wrath at Roshal’s attack on military forces during an engagement—but like the Walled Cities, it missed the forest for the trees. Both the House of El and House Terland added their voices of displeasure to the calls, mainly due to Deilan El and Lord Xitegen, but they made the opposite mistake.

They complained too early. Before they could spell out exactly what had happened to Erin Solstice—and even afterwards, there was no proof.

A riddle for the Titan of Baleros. Or Magnolia Reinhart when she’d finally pulled enough shrapnel out of her midsection to focus on the problem.

Who had seen what went on in The Naga’s Den? Who could paint a clear and unequivocal picture of the horrors that had gone on and testify?

Well, it was either the [Slaves], who had vanished; Erin Solstice, who was public enemy number one; Ulvama, who was a Goblin, the dead [Slavers]—good luck there—or maybe House Shoel of Ailendamus.

Explaining how that last group had seen what was going onboard the ship was something none of them were keen to do, and Roshal focused on them exclusively. Whatever deal was arranged between House Shoel and Roshal was probably one of mutually assured destruction. Both sides had too many secrets to spill.

Soft power. A gentle touch. Just enough deniability here or a delay in someone shouting there to keep Roshal’s name quiet. At least, when it came to kidnapping.

Assassination? Go ahead and talk all about it! Everyone had [Assassins]. That was fine. Kidnapping looked far worse. And people could talk about Roshal.

Why, even the Chandrar International had a huge image of the destruction in Lailight Scintillation. A harbor filled with dust; ruined buildings. Death wrought by Khelt on an unimaginable scale that only the most enchanted buildings had survived.

Normally, Rémi Canada would have loved to point out exactly what Roshal had done—but Erin Solstice was missing, and he had no proof. And the attack on Roshal was news he had to deliver.

Worse—he’d been invited and given access to interview whomever he wanted. Even if he tried to spin an angle by talking to [Slaves], he still had to show people the ruined harbor. And that picture overwrote all the other news of Roshal assassinating a few Humans somewhere.

Perhaps the [Journalist] even knew he was falling into a trap. He certainly avoided the person who’d orchestrated everything from Zeres’ contract to his invitation.

——

Shaullile Rubyscale was a Drake. Also a [Slave Lady] of Roshal. Definitely not a long-dead ghost from ages past. Certainly not the manager of Roshal’s entire diplomatic arm and public relations branch.

They hadn’t even had a branch until she came along. It had been individual, cunning [Emirs] like Yazdil doing whatever they thought was best, not organized, coordinated actions.

Perhaps that had served Roshal well, but Shaullile foresaw a future in which having a far more capable group of people would be needed to curb any…incidents that might occur.

After two weeks of monitoring the individual groups trying to raise the news about what Roshal had done, she declared a tentative victory. Forgotten Wing had been the loudest, but they were a [Mercenary] company and far removed from Izril.

Now came the counterattack, or at least, groundwork for it.

Shaullile had just finished hand picking her team. That was to say, eighteen ordinary citizens of Roshal, twenty-nine [Slavers] who had agreed to take lessons from her, and fifty-eight [Slaves].

Well, former [Slaves]. At this very moment, they were having the collars removed, the registry was being updated to show they were free, and they were even being issued markers to prove to any overzealous [Slaver] that these people could not be chained lest the wrath of Roshal fall upon them.

Shaullile always got a bit emotional when she saw the collars being removed. The expressions of radiant joy, disbelief, were so…wonderful.

She had a few pictures taken. Let them hug her—and assured them they would not only relish their new freedom, but truly come to love working for her.

After all, it might have confused Pazeral, but Yazdil had understood in a flash that there was no better person to espouse Roshal’s beauty and greatness than a former [Slave] who worked their way from the bottom into freedom, and had even achieved the dream of owning other [Slaves] themselves. How bad could slavery be if a freed [Slave] participated happily in the system?

Especially if they were attractive, well-spoken, and the same species as anyone they were attempting to sway.

“How has Roshal forgotten all the old tricks? I suppose they did well enough before me—but standards have fallen.”

What they needed was goodwill. What they needed were children covered in the dust and ash of Khelt’s attack spell staring wide-eyed into the scrying orbs and asking why Fetohep of Khelt had killed their entire neighborhood.

That was how you won wars before [Soldiers] marched. The grief and pain of the attack on so many civilians—that was real. Shaullile herself felt wounded by Khelt’s spell. There would be blood for it, but she was no warrior or strategist in the sense the others were.

She defended Roshal and attacked in ways that seldom drew visible blood. However—Shaullile stopped and checked her appearance as she stepped onto a platform raised and lowered by a Djinni, speeding towards the top of a tower for a meeting. She smiled at her reflection in the glass.

If there was anything she craved and loved, it was the ability to speak to a people and convince them. To see Roshal’s flag fly over a Walled City again would be a triumph. Once that was done—

Then she could indulge herself. But the Drake was all business, even more than Andra. So she strode into the meeting perfectly on time. The other Slave Lords of Roshal heard her report out.

“And how much will this cost us?”

Andra was preparing another budget, and Shaullile quoted a number.

“Low. Do you need more coin?”

Yazdil raised his brows, and Shaullile gave the Naga a sweet smile.

“Using coin in the place of tact or manpower is a crutch, Emir. Save it for when you need to stop a Walled City from declaring war. I have thwarted almost all the repercussions coming our way in a public sense. Individuals will remember, but our reputation is safe—not least because of Khelt.”

She would never have said it out loud, but the Tier 7 spells dusting the harbor had actually been a boon compared to a conflict. The other Slave Lords wouldn’t have wanted to hear it, though.

Each one regarded the attack as a personal wound against their beloved home. Thatalocian had taken the blow the most seriously of all. He sat hunched, eyes narrowed, and Shaullile wouldn’t want to be Khelt right now. For various reasons.

She refocused their attention on the obvious, though. They might be out of danger, but there were players on the board, and she didn’t like the one who had gotten away. As far as Shaullile was concerned, it was time to break out the [Assassins]. All of them.

“If Erin Solstice appears—that will be the most dangerous moment. Her reputation must either remain tarnished or we’ll need to address her if she returns. Not my business. Just keep your noses cleaner, will you? Excuse me—tails. Drake aphorisms.”

She sighed and leaned back in her chair as the other four rulers of Roshal agreed, more or less equitably.

Pazeral barely cared about all the work Shaullile had done; the [Lord of Possession] was still fuming over the combined defeats he’d suffered, losing Erin and at Liscor.

Yazdil was even more angry still, having lost Iert and his ship, but he was silent. Controlled.

Andra was simply listening with one ear, continuing to do business as she understood it, which was sums of gold and land and people, working her way into the spine of Roshal’s economy, especially with it so damaged.

And Thatalocian? The [Numerologist] just sat there. He stared at Shaullile, who gave him a charming smile, and his gaze was flat.

“Public…relations. In the days of magic’s death, we needed it not. Roshal was one candle among the few remaining. Our works were good.”

“If you wish to win us some supporters with some virtuous action, don’t let me stop you, Lord Thatalocian. But please let me know so I can advertise it properly.”

They were two different kinds of Roshal, he and she, but she gave him a huge smile, and he grudgingly nodded after a moment. Thatalocian’s eyes narrowed, though, to pinpoints of light.

“This is your talent and Skill.”

Shaullile had lived through the first rebellions of Stitch-folk, presided over a Roshal when they had tried to suppress the new people. She had failed—but her eyes glinted nevertheless.

“I’m quite good with people. Yes. Why?”

The [Numerologist] smiled mirthlessly.

“You have a Skill. A Grand Skill. All your cunning and the disunity of others is not enough. I count one power set against the disunified numbers. An auspicious value.”

The other [Slave Lords] looked at Shaullile sharply. She sighed.

“Yes, well, it can’t work against anything too visible. If you must do it—”

She leaned forwards.

“Do it subtly. Or I will eat part of you.”

The Drake gave them all a sharp-toothed smile. Then Pazeral did smile, and Andra nodded. Yazdil just narrowed his eyes as if trying to guess her Level 50 Skill.

[Suppress the Truth, Smother the Facts: Protect Reputation (Roshal)].

So long as she lived, and so long as nothing too egregious occurred, Shaullile could stop anything short of a direct attack on Roshal’s name. At least, where the public was concerned. Individuals were harder, but public opinion? That was invaluable.

And she could persuade individuals herself. That made her one of the greatest [Slave Lords] to exist.

——

Nuvityn saw it. He stood there, confused.

“A [Necromancer] the likes of which no one has heard of. A kidnapping to sea by Roshal. Then she sails into a war between [Pirates] and Terandria and makes her way to Ser Solstice. Slays…Iradoren. Vanishes as the world tries to destroy her, only for the Death of Magic herself to save her life. Who is she?”

“A child of Earth.”

Voreca’s answer made sense, yet it was wholly inadequate. Nuvityn had met Earthers. They did not have the eyes of men and women who had killed and changed forever. They could not stare down foreign rulers.

“Tell me more. Tell me more of the woman who killed my son. Then tell me, Voreca, why she lives.”

Heavily, the King of Myths sat, and the answers came to him.

“We have few agents in Baleros, Your Majesty. What few we had—the Forgotten Wing company is led by one of the world’s greatest [Rogues]. She has a Fraerling escort.”

“Why?”

No one had answers. But now, King Nuvityn felt it. That numbness, that incredulity and emptiness turned to a more comfortable feeling, however poisonous in his belly.

Wrath.

He began to rise to his feet.

“She killed the Prince of Erribathe. Does the Titan of Baleros shelter her? Is there not one [Assassin] in Baleros willing to take our coin?”

“The bounty on her is already high, Your Majesty. Ratified by other nations. Khelt among them. The Blighted Kingdom—”

Nuvityn’s mouth stopped as he began to utter an amount that would drive even commonfolk to try and murder her. He halted, though it was not easy to quell the words in his chest.

“Roshal.”

Thence he sat again, arms folded.

“They kidnapped her onto their vessel. Tell me honestly, Voreca. I ill-like to accord anyone sympathy. But is there a chance that the vessel, The Naga’s Den, was not a [Slave] ship?”

She hesitated, but the folk of Osverthia spoke truth.

“I cannot imagine it were anything other than that, sire. It could be she was treated like an honored guest.”

“Can you prove that?”

He doubted it. One was not kidnapped into luxurious treatment. He remembered something else.

“She had scars around her neck and wrists when she was…not now. Is that true?”

Someone found a still image, and he saw a young woman with clearly burned skin steering a ship through the storm. Nuvityn’s eyes narrowed.

“That man standing next to her. Who is he?”

“Viscount Visophecin of House Shoel. Ailendamus, Your Majesty.”

“Ailendamus.”

There was some kind of puzzle here, and yet the King of Myths didn’t have the canniness to uncover it. He understood parts, he supposed.

“So this Ser Solstice, who bears her name, was important enough for her to sail against [Pirates] and even Terandria for. No…she was not clashing with Terandrians until the end.”

“Not until Prince Iradoren attempted to capture him, sire.”

One of the Kehndroth [Strategists] spoke. They were nomads, by and large, with fierce tempers and fine horses, arguably as good as Voreca’s folk despite the latter’s heavier armor. Nuvityn looked over and saw blazing, red-rimmed eyes. Dusky face. Braided black hair.

“Andromeda.”

He was surprised to see her here. He would have assumed she’d remain with the funeral processions. Clearly, she mourned his loss.

“I was there with Prince Iradoren, Your Majesty. He wished to capture Ser Solstice—”

“Kill.”

Nuvityn interrupted her. She protested.

“Not initially—”

“Kill. He swung his sword to kill. Against a [Knight] who proved his valor in battle time and time again.”

That was part of the reason why all of Terandria was not still crying for the [Innkeeper]’s death. Andromeda’s voice lowered.

“It was with good reason, sire. If he was—”

“A Goblin. You have said. The fact remains that he had no proof. A war was raging, and he chose to execute a single Goblin who had not drawn his sword against anyone present.”

“If it was a Goblin—”

“One Goblin was not an army of [Pirates].”

He didn’t realize he’d raised his hands until they came down and the entire magical map flickered for a second. The room thundered, and Andromeda fell silent.

My hands hurt. Nuvityn shook them out. He was ashamed then; a [King] should not rage. He wondered who he had been shouting at.

Andromeda? Himself? Iradoren?

How could he shout at the dead? But his son had made a mistake. No matter how Nuvityn looked it over, he could see him brandishing his blade as a [Princess] literally covered Ser Solstice with her body. The King of Myths put his head in his hands a second.

Yet the rage would not abate. Ser Solstice. Erin Solstice. Princess Seraphel of Calanfer—

They all had much to answer for. If only there were [Pirates] left alive to hunt. There were a few, but—

“I shall remove Strategist Andromeda from the room, sire?”

Voreca offered, and Nuvityn shook his head.

“No. She has the right to stay. Let us move on. Assassins have been called for.”

“Is it your will to increase the bounty, Your Majesty?”

His lips moved as he thought out loud.

“It is not my will to take Roshal’s side. Is the bounty sufficient to attract any [Assassin] of renown?”

“Yes, sire.”

“Will increasing it change many minds?”

“…Unlikely, Your Majesty.”

Then it will be our agents or none. He waved a hand and thought. Then he had another question.

“The inn.”

It was petty. Vengeful, but did he not deserve it? Andromeda’s eyes lit up, and Voreca shifted, glancing to the side. Nuvityn’s voice rose.

“Why does the inn still stand? Can we not destroy that at least? With a spell?”

He would sacrifice ten Tier 6 spells to rid the world of that building. In a heartbeat. He turned, and a dry, deep voice spoke.

“Not easily, sire. The inn belongs to Liscor and is protected by Pallass and House Reinhart. There are other factors.”

Nuvityn turned to another old friend. This one older still. He met the eyes of a half-Elf, one of the few people who could live as long as he. This was Miihey. A half-Elf with tanned skin, arms like bars of steel, and old scratch scars all over his body.

He was bare-chested, smelled like the forests he came from, and hailed from Forem. Most half-Elves lived in their enclaves, but here was a wildling from the tribes who wrestled bears and lived in nature. [Barbarian], they said.

Advisor in the Kingdom of Myth’s courts. He was also, like Nuvityn, plain-minded. But not uncunning.

“We have cause. Order the inn evacuated and turn it to ash. Why was it not done already?”

“They will not go, Your Majesty.”

“Then send a weaker spell first and let them flee ere it becomes dust. Why hold back?”

Andromeda was nodding. Again, Nuvityn heard it like a clear call to arms. Words of wrath—Voreca glanced at Miihey, and the half-Elf spoke.

“Because children run the halls.”

The King of Myths, wrestling with his anger, suddenly felt his opposition vanish. He leaned over the table.

“Ah.”

“We could fire a warning—”

“No, Andromeda. Are we true savages? Miihey, you have the right of it. Children. I thought you said that inn was constantly attacked, Voreca. Why would anyone allow children inside it?”

“At least two have nowhere else to go, Your Majesty.”

The King of Myths closed his eyes as she briefly explained. Ah, there it was. Intentional or not, the [Innkeeper] had a simple bulwark ‘gainst any decent foe. He opened his eyes.

“Who resides in her inn who still claim her?”

He listened to a brief description. More Goblins. Antinium…and then his eyes narrowed.

“The 6th Princess of Calanfer? Truly?”

One of his advisors ducked their heads cautiously.

“Without a doubt, Your Majesty. We approached Calanfer over the issue—they have been typically obtuse despite our pressing demands for clarity.”

“Why an inn?”

No one had good answers. Now, frustration was warring with rage. Something had to be done. Decency would not stop wrath of some kind.

“Your Majesty does not intend to let the Prince’s death go unavenged, does he?”

Andromeda was straying close to true insubordination, if not already over the line, but one glance at her face and Nuvityn wondered if she had wept the entire month. Perhaps she and Iradoren had been closer than he thought. His tears had dried up it seemed.

“Never. But I see how quiet Erribathe’s voice has become. Once, if we spoke, the Walled Cities would listen. Now?”

They had made overtures to Pallass about the issue. Nary a response back. Erribathe was distant. Few people remembered the Kingdom of Myths outside of Terandria’s shores.

“They remembered us when the Goblin King sailed against their continent. We sent forces to Izril’s shores to fight and die to stop the Goblin King. Just as we hold against the Demons.”

Voreca’s voice was equally bitter, and provoked nods from many. Nuvityn just shrugged, hearing his grandfather’s words in hers.

“‘Better to lie sleeping as a Giant than to wake and die.’ This era changes us all, Voreca. A Dragonlord spoke at Calanfer. My son heeded the call. Now I?”

He stood there bitterly, looking around. Erribathe had not seen strife in his lifetime. Not true strife. Even Az’kerash had never made it to Erribathe’s heartlands. If anything, the threat of the Archmage of Golems invading Terandria had seemed worse at the time, and the Demons.

Now, though…he thought of Erribathe. It needed a king. But it might not need him. He had intended to let Iradoren grow in the New Lands of Izril, then cede the crown to him. Live out his days in some other pursuits. Learning to hunt for a living, perhaps.

“Erribathe has no arms beyond where it can reach with its own soldiers. But we are no helpless nation. I will not let this go unanswered, no. Send word to each land. I will muster a force. A small one.”

“Sire?”

Voreca sounded alarmed, and Nuvityn clarified.

“Ten thousand. Those willing to ride with me for the [Prince of Men]. For judgment. For war, if it comes upon us. We go hunting. And if an army stands between us and our quarry—”

His eyes focused on the glowing icon in the heart of Baleros, then on Izril. Which one? He dismissed them without a thought. It would take time to muster the provisions.

“You intend to leave Erribathe, Your Majesty?”

The other advisors were excited or alarmed, but Miihey had noticed the important part. Nuvityn looked up.

“Yes. I am not ready—yet. A week. In a week’s time, we will ride. Assuming all those I intend to join me are able. Voreca, send word. Gather a host that would sail to Rhir itself. But remember—”

He stopped Andromeda before she strode out of the room.

“It will be an army with tempered blades. When we judge, it will be fairly. My son, the [Prince] of Erribathe, is dead with so many others. We balance those scales.”

Then he felt better as his spine straightened. The King of Myths stared at the faces of those around him and saw them focus on him. He took one breath. Then two, and he felt that heavy weight of guilt and loss around him. But his shoulders fell back, and he felt—

Invigorated, poor as that was to feel. A calmness upon him.

I will find that [Innkeeper] and settle my grief past Erribathe’s borders or die. Even if I must take all of Baleros and Izril to battle.

Ten thousand of Erribathe’s finest. He would put them against an army ten times that size in a heartbeat. But—the King of Myths flexed one hand.

“Saddle my horse. Tell the Village of the Spring I wait on their words.”

He had been intending this, he realized, the moment he saw his son die. Without a word, King Nuvityn strode from the room.

——

He did not immediately leave the capital city of Terinloth. For a while, the King of Myths walked through the streets that had been first paved in the days when Elves and Giants walked Terandria.

—Of course, all the original stones had worn away. Even magic faded. So little could withstand the weight of so many years, and Nuvityn thought that Erribathe itself was probably a shadow of what it had been, or so changed as to be foreign to the [Kings] of ages past.

That was fine. Something that Nuvityn had learned over centuries of life was that change was alright. Both in himself and the world beyond.

He asked questions on the days when the despondency of ruling his sedentary kingdom year after year got to him. And it was always this:

Are they happy?

Not just ‘do they look happy’, because happiness could be faked. Were they happy? Nuvityn had met loyal subjects who groused every day of their lives.

“Good morning, Sommete.”

“Is it, Your Majesty? It’s good to see you about. Rumors are a terrible thing.”

The [King] strode past a [Grouchy Grocer], who might have engaged him in further complaints about the weather, the state of the world, and the foibles of young and old people alike. The middle-aged man ran an open-air shop close to the palace.

He was exceptionally popular. A crowd of people bowed or waved to the King of Myths; most, Nuvityn recognized by face and name. Sommete stood there, a scowl on his face, and turned to the first person in line.

“What are you smiling about?”

“Seeing you finally cut your exorbitant prices on tomatoes is a good start.”

A Dwarf put an elbow on the counter sized for shorter people and treated Sommete to an even wider smile. The [Grocer] scowled harder.

“I should raise it back up! The amount of work I do for you people to get prices competitive, and I get sneers instead of applause.”

“Would you like applause? Well done, oh mighty Sommete. I’ve not seen a man burdened heavier this entire year. Oh, good morning to you, Your Majesty.”

Laughter followed Nuvityn, and the [Grouch] huffed harder as Nuvityn smiled despite himself. Sommete was well-liked because he was a kind of magnet for bad vibes. Even now, Nuvityn couldn’t tell if it was all some act or if he was genuinely upset about stepping in a puddle last week. Either way, if you did it respectfully, throwing verbal jabs at the man in the morning was how some citizens like to start their day.

Citizens. Nuvityn was a tall man, but he wasn’t the tallest walking the street. A half-Giant stopped as she began to cross the street; she was using a dedicated crosswalk reserved for people her height. She began to bow, and a gaggle of Dwarves did likewise.

Half-Elves. Humans. Dwarves. Even a small, small population of half-Giants made up Erribathe’s people. That might not actually be the most diverse, but for Terandria, it made Erribathe practically unique.

Not only that—the subraces of humanity practically qualified them as different peoples on their own. You could always tell who was new to Erribathe. When the tribes folk came down from the hills, they stood out like a sore thumb compared to those from other cities.

They all recognized Nuvityn, of course. One of the warriors wearing woad markings raised a blade and ululated, a piercing, sorrowful cry taken up by the entire band come to the city to trade.

“Your Majesty. I can have them stop—”

“No.”

Nuvityn forestalled Voreca from silencing the cry, and he raised his own fist overhead. He answered with his own modulated warcry. A somber, painful sound that surprised him. But Torek’dale’s hill tribes believed each person’s voice was honest.

They lowered their heads as he nodded to them. Nuvityn pretended to be on important business; he didn’t feel able to exchange words with them.

The answering cry was enough. The citizens of Terinloth gazed at their [King], and Nuvityn saw a mix of grief, sympathy—the [Prince] of Erribathe was dead, and mourning had been long this month. He had shown himself little, so small wonder so many wished to speak to him.

What he didn’t see much of, thankfully, were the expressions on a pair of visitors from other parts of Terandria.

Taimaguros. They were clearly from Taima; that divided nation made the two sides war like Drakes and Gnolls. The visitors looked positively aghast at seeing a [King] from the Hundred Families utter a war cry like a low-class [Barbarian].

Possibly, that was why Nuvityn decided to add a second salutation to the warriors. He shouted at the men and women who wore war paint and hide clothing.

“Torek’dale an misghet! Salvit Torek agn!”

They whooped at the simple greeting—’warriors of Torek’dale, salute to Torek!’. Nuvityn didn’t know the full extent of their odd quasi-language. But he had learned it.

The faces of the two noble visitors was enough for him. If ever a day came when he saw that expression reflected on the majority of the citizens in the capital, for any group of Erribathe—that day, the Kingdom of Myths would plant the seeds of its own destruction.

They were one of the Restful Three. The great kingdom who had taken war to other nations. Seen Dragonlords felled and survived the calamities of ages, from the death of magic to the imperiums of other nations to the Creler Wars.

Past the capital city, you could see the mists rolling across Erribathe. Each morning, they descended on the outer third of Erribathe, cloaking the sky. Any intruders without the ken of navigating them would quickly become lost. Armies had blundered around and been slowly taken to pieces as they became lost for months.

It was one of the defenses of Erribathe. The other was the spread out peoples, each one different. Torek’dale were still hill-folk who refused to live in buildings of stone, despite having thousands of years to change as they willed.

This made them happy. Osverthia, by contrast, was a region founded on the supremacy of metal, and they often competed with Deríthal-Vel for work outside the kingdom.

It was not perfect. Not by far. Erribathe was not a paradise; it had monsters. If anything, the magical kingdom seemed to attract them, and the different peoples sometimes went to war, despite the King of Myths’ attempts to keep order.

But the font of Nuvityn’s nation was that the peoples within at least respected the prowess of the others. Osverthian [Knights] were unmatched for their armor and heavy charge. But Torek’dale’s prowess in hand-to-hand combat and their magics would make any jest about them quickly fall flat.

If Nuvityn looked across his city, he could see old bridges of stone reaching over huge canals along which more buildings opened into the rivers.

Once, those rivers had had a people of their own. No longer. There had been a time, he knew, when the air had contained Harpies and other winged beings.

Erribathe was smaller than it had been. But the survivors of each race who had watched Treants walk into the sea and the Dryads abandon the forests were not idle.

Preserving majesty. It was why you saw Voreca’s people, Osverthians, fencing already in the morning, practicing the swordplay of their ancestors, trying to master the sword schools of old. It was not in expectation that Erribathe might be attacked. If anything, the warriors would dream of being sent on a crusade or to aid another Terandrian kingdom.

It was living up to the stories of their predecessors. The Hundred Heroes—the many Osverthians who’d joined the Thousand Lances. [Heroes] and [Champions].

That was what made the capital city of Terinloth unique. The memories were everywhere.

Cross the third southernmost bridge over the canals, walk through the place where the city branched over to an island filled with half-Elven buildings in greenery. But don’t walk down that street; pass by one of the old walls that no longer formed any kind of protective barricade.

Several sections were still there, maintained painstakingly despite their lack of relevance because of the murals.

—An image set in tiles of a [Knight] tilting against a Dragon, whose own body bore a lance but no rider. The Tourney of the Dragon-Knight, in which Erribathe had seen a great competition of heroes vying to join the Silver Dragon-Knight in his quest to rid Chandrar of one of the Crypt Magisters.

Several parts of the wall had collapsed despite the best efforts of [Masons], but the entire story had been painstakingly recorded in many formats. Even now, you could sometimes find children staring at the glittering tip of the [Knight]’s spear, set with a single piece of mithril, and watch their eyes widen.

If he ever saw that, the King of Myths would stop and ask them if they thought they could have been one of those [Knights]. If they were bold, they’d say ‘of course’. If they lacked for confidence, they’d demur or explain some failing of theirs. Then the King of Myths would tell them to seek another story in the city. That of the Sightless Ranger, or perhaps the somber tale of the King of Trolls. You could live a life of adventure reading the stories and dreaming—

He had been a young man like that once. Racing from sight to sight. Nuvityn wished he could forget all the stories so he could experience them again and feel that heady rush.

That was also why he was a poor father, perhaps. His own father had done what he felt was best: taught Nuvityn the ways of the sword and as much magic as the King of Myths could stand. Given him the finest tutors in leadership, strategy, and the lessons of kingship.

But King Reseclor had been troubled and wearied by the horrific advent of the last Goblin King, Curulac, and rebuilding from the havoc Curulac of a Hundred Days had brought to Terandria had made him a distant king.

It had still worked. Nuvityn had grown up a wild boy racing about the city with a gaggle of his friends. He’d made his mistakes, gone on stupid adventures and won stupider prizes—and fumbled his way into kingship with Eithelenidrel. Left her unhappy and been restless and foolish until time had weathered him into a better ruler.

—Then he’d had his son. Well, he’d had his son while doing all this, and Nuvityn had had the chance to raise the boy in a more peaceful time, and he’d decided not to change what he had felt was a working formula.

Iradoren had grown up free to explore his homeland like Nuvityn. He had not wanted for companions and lessons, but Nuvityn had let him choose his path.

And that boy had stared at the image of the [Knights] on glorious quests and asked why Erribathe was not ruling countless satellite nations, and why the old colonies had been abandoned. When Nuvityn had pointed out that the King of Destruction had emerged from Terandria’s ambitions in Chandrar and the cost in lives to make war against other nations, Iradoren had told him it was acceptable.

‘The glory should be worth the cost, of course, Father.’

The cost. Hearing his son talk about that and seeing how he aspired to place Erribathe above other nations had kept Nuvityn from preparing Iradoren fully to replace him on the crown. When the news of Earth had come to them, both had rejoiced. To Nuvityn, it had been a sign, a way for Iradoren to channel that restless rage that possessed him instead of having to wait a century for his ambitions to rest.

Then…

Nuvityn realized he’d stopped amidst the humble, winding houses near this wall in the southeastern section of his city. The buildings here were old, and the ancient masonry was prone to dust. The streets often needed sweeping.

The King of Myths had been staring at the image of the tourney of knights so long that someone had come slowly down the street. An old [Sweeper]. A half-Elf paid by the city to do a simple job of keeping the streets clean.

She was old. Very old. For a half-Elf outside a village? She was over a thousand years—white haired, but largely unwrinkled. Yet time made her movements slow, and she swept quietly as she passed by the King of Myths. His entourage held back, respectfully, and the half-Elf eventually ended up sweeping a circle around Nuvityn’s boots.